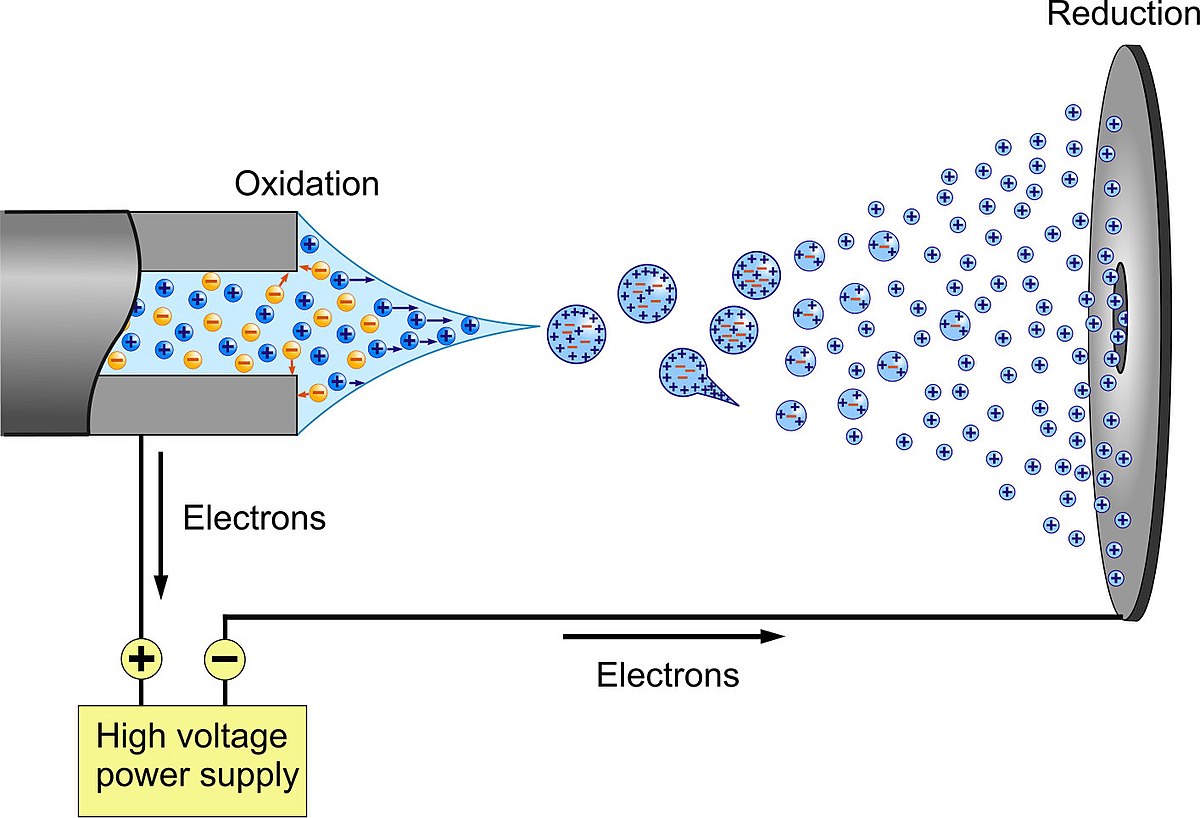

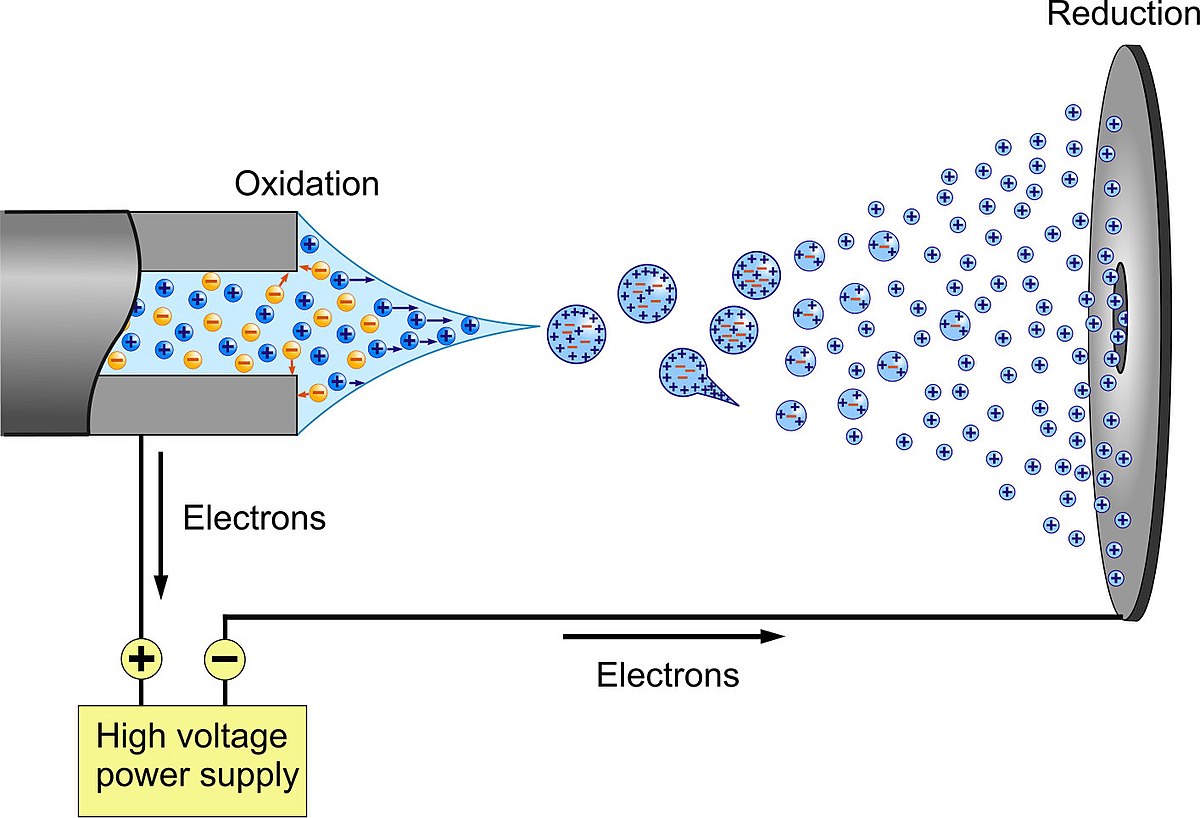

Since mass spectrometry involves getting molecules into the gas phase and ionizing them, one might think that large molecules with a very low vapor pressure are not susceptible to characterization using this technique. Not so! Chemists can be very resourceful in getting around seeming roadblocks like this. It turns out that a technique called electrospray varporization solves the problem. Here is a graphical overview.

Image of electrospray ionization. Image courtesy Visualize Your Science at https://flickr.com/photos/136533650@N02/21589986840.

Often what occurs is that the protein or DNA molecule is injected in a buffer solution comtaining salts, and as the droplets fragment, there may be a single biomolecule in a driplet having an excess of, say, sodium atoms. As the water evaporates, the excess charge basically blows the droplet apart. Some of the biomolecules hang on to the sodium (or some excess protons) and wind up thus ionized. They can then be steered into a mass spectrometer.

|

Once ionized, biomolecules can, of course, undergo the same fragmentations that other organic compounds do. While a complex problem, the mass spectrum contains enough information that often a protein can be sequenced by analyzing it's mass spectrum. More complex information can also be obtained, for example looking at D2O exchange reveals what parts of the biomolecule are in contact with solvent under different conditions. In some cases, small molecule binding can be determined or the effect of chemical modification monitored.

See a recent paper from Prof. Claudia Maier on protein modification.

|