Background

This section explores Calibrated Peer Review and physics education research pertaining to the use of group activities, student writing, and using a rubric.

Calibrated Peer Review

Calibrated Peer Review is a writing process allowing for in-depth writing assignments with minimal load on the instructor. To ease the load on instructors, CPR has students peer review one another's work using a calibrated rubric. The steps for setting up a writing activity using calibrated peer review requires three essential components.

First, the instructor creates an instruction sheet for the writing assignment, including a list of source material from which students draw to address the writing prompt as well as a set of guiding questions to direct students when addressing the assignment. The instructor then creates a rubric for students to use in peer evaluations. The rubric typically include yes or no questions, such as, “Are there at least three reasons given to support the use of SI in the scientific community?” Finally, the instructor creates three benchmark samples of varying quality and scores each with the rubric that the students will eventually use. Each of these components are developed online using the website provided by UCLA, which is as of now free.

At this point, students are ready to use the CPR developed writing assignment. Students start by reading the instruction sheet, providing them with guidance on what they need to write and the source material from which to draw their information. Students then begin the text entry stage of CPR where each submit their own essay using the online program.

After submitting their own essay, the students are given access to the rubric and the benchmark samples and asked to score each paper following the rubric criteria. This is known as the calibration and review stage. Students submit their scores and receive instant feedback on how well they were able to score each paper. The students then use the rubric to score other students' work, and then score their own submitted essay. Grades for each paper are assigned based on a weighted average of the peer evaluations. Students who followed the rubric well when scoring the benchmark papers will have a greater weight in the average score, and students who did not score the benchmark papers well will have very little weight in the score of the paper. This aspect of CPR mitigates the common problem of “the blind leading the blind” when using peer evaluation as a form of grading and feedback to each student.

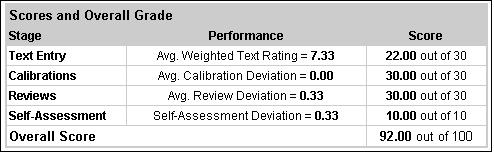

When the assignment has been completed by all students, the results stage of CPR begins. In this stage, the program determines how well the student scored their peers by calculating their deviation from the average. The instructor chooses a maximum allowed deviation; students below this threshold are considered to have mastered the evaluation process. Each student can then read each of their peer reviews on their own paper, and compare it with their self evaluation. An overall score is assigned by the program which compiles the quality of four criteria: text entry, calibration, reviews and self-assessment. The average weighted text rating is the score for the text entry criterion, and the students' deviations are used for assessing the quality of the other three criterion. Deviations are turned into a score and averaged with the other criteria for an overall paper score. The table below is an example of what the student sees at the end of the review stage.

It should be noted that in a standard Calibrated Peer Review process, the instructor is never required to read any student papers; all of the grading comes from the students. It is also important to note that a large portion of the grade comes from evaluating other work, not the quality of the paper the student writes. A student could submit a very poor paper, and it would only bring down the average overall score marginally as compared to if the quality of the paper were the only grading criterion.

Prior Research

There has been a great amount of research done on student's ability to write about science, use rubrics to evaluate writing, small group activity work, as well as research determining what affects student ability to understand and communicate an understanding of science. Research in a school in South Africa found that writing about science improves when nonlinguistic means (such as demonstrations) are used in conveying ideas, and that explicit guidelines are important for students to be able to produce good writing (Kaundra, 1998). This investigation also reports that the quality of scientific writing is proportional to the amount of time available for the completion of the assignment. The authors of this investigation assert that, ”…an understanding of the procedural aspects of an experiment is as crucial to the production of a good report as an understanding of concepts is in the production of a good essay.” Writing assignments implemented in the paradigms courses did not involve any experimentation, but it is important to note that without a good understanding of the concepts with which each activity involved, a student will never be able to produce very good writing.

Physics education research carried out in an introductory physics course found that “better problem solutions emerged through collaboration than were achieved by individuals working alone.” (Heller, 2008) This is important to the paradigms project because students worked in small groups when completing the activities on which they based their writing. Because more complete and expert-like solutions are produced by students when working in groups, it seems to suggest students come away with a better understanding than when working alone, and definitely are able to more clearly express their solution which is integral to the writing process.

One final important piece of research involved implementing traditional CPR in an introductory zoology lecture class. What researchers found no data to support that students' technical-writing skills improved, nor did their abilities to convey scientific understanding improve. Furthermore, grades received via the CPR process were consistently higher than instructor feedback scores alone. Though implementation of CPR in this research seemed to not aid in goals the paradigms project seeks to achieve, the authors of the paper have noted that, “The best uses of CPR may be for assigning questions requiring more objective answers (especially in introductory classes); in coordination with group work in some hybrid setup; and/or for refining already “good” writing skills in upper-divisional courses (where more subjective scaling could be used).” The authors also stress the importance of writing rubric questions that “are concise and cover all important criteria for the writing assignment” and “to craft writing prompts that support course goals.” These reflective comments are especially important to this research since the paradigms students worked together in groups when completing their activities, are all upper-divisional, and usually have at least one course in honing technical writing skills prior to entering the paradigms classes.